Conflict

and Harmony

Conflict

and Harmony  Conflict

and Harmony

Conflict

and Harmony

---- Review upon A Passage to India

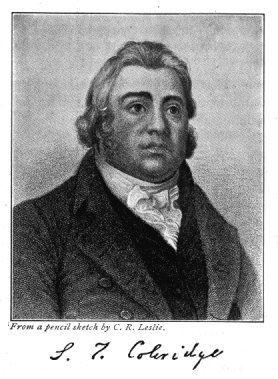

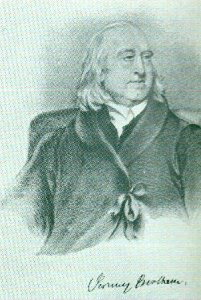

I A Coleridgean or A Benthamite?

Every Englishman of the present day is by implication either a Benthamite or a Coleridgean.

-------John Stuart Mill

It may be that civilization will never recover from the bad climate which enveloped the introduction of machinery.

-------Alfred North Whitehood

The division of Coleridgean and Benthamite may perhaps be considered as the divorce between thought and feeling. T. S. Eliot claimed that the divorce was one of our evil inheritances from the Reformation. To label Coleridgean and Benthamite might be a too great task for me. Indeed, when you are asked what is the first law of political economy, and you recite the Golden Rule, the question is Benthamite, and the answer Coleridgean. The split of the two parties is essentially a contrast between a mechanical and an organic view of life, between analysis and creative synthesis, between rationalism and romanticism, and denotes the split personality of an age------a serious tragic separation between the practical and the ideal. Coleridgean and other idealists wanted to heal this separation of schism by repudiating its causes------not through legislative reform or social action, but through ideas and art.

E. M.

Forster is an implicit Coleridgean. He is dedicated to the search of Poetry,

Religion and Passion. The three words are not synonymous, but they are

inseparable ---- the holy trinity of a romantic humanist. Thus most of his

novels pay little attention to political affairs. He just wants to describe

that the humans live by clock time rather than geologic time and their politics

is only clouds of dust on the eternal plain. His last (non-posthumous) novel, A Passage to India, is also to make

people and their politics look small and to see them as petty actors on a

gigantic stage. This novel is claimed to be a great work of understanding.

After finishing writing this novel, he stated,“I somehow dried up after the

Passage,

I wanted to write, but didn't want to write novels.”

E. M.

Forster is an implicit Coleridgean. He is dedicated to the search of Poetry,

Religion and Passion. The three words are not synonymous, but they are

inseparable ---- the holy trinity of a romantic humanist. Thus most of his

novels pay little attention to political affairs. He just wants to describe

that the humans live by clock time rather than geologic time and their politics

is only clouds of dust on the eternal plain. His last (non-posthumous) novel, A Passage to India, is also to make

people and their politics look small and to see them as petty actors on a

gigantic stage. This novel is claimed to be a great work of understanding.

After finishing writing this novel, he stated,“I somehow dried up after the

Passage,

I wanted to write, but didn't want to write novels.”

What can we derive from this Passage?

II. The Outer Passage

I am glad to have known our countryside, before its roads were too dangerous to walk on and its rivers too dirty to bathe in, before its butterflies and mild flowers were decimated by arsenical spray, before Shakespeare's Avon frothed with detergents and the fish floated belly-up in the Cam.

-------E. M. Forster

-------E. M. Forster

E. M. Forster was a Coleridgean who lived and wrote in an increasingly Benthamite society. The meddlesome manipulations of modern man had destroyed more than they had built and the bargain between people were destroying love. Modern progress had been a rape and the Politics and economics did not deal in spiritual compensation.

Forster saw the imbalance of modern life and wanted to correct it. Thus in A Passage to India, he tried to build up several kinds of harmony all Coleridgean dreamt of. Most harmonies were somehow produced in the form of trinity.

The first trinity is earth, sky and water, which cooperate briefly for peace and harmony of the secular world.

You may have noticed that the three sections of the book, Mosque, Cave and Temple, are actually a wonderful trinity which plays perhaps the most important role in this book. The section of Mosque is about the cooling season in India, that of Cave, the hot season, and Temple, the rainy season of monsoon. Yet it is in the season of monsoon that the harmony between sky, earth and water is obtained and that Fielding held Aziz affectionately, "Why can't we be friends now? It's what I want. It's what you want." Moreover, on the human level, the trinity of Mosque, Cave and Temple indicates another important triad of the book, that of Moslem, Anglo-Indian and Hindus. The Hindus are relatively withdrawn from social and political contentions. "They are circles even beyond these------people who wore nothing but a loincloth, people who wore not even that and spent their lives in knocking two sticks together before a scarlet doll."

The Moslems are somewhat more active, their representative, Aziz, is a fretful mixture of love and hate, amity and hostility, and he is longing for "the hundred Indias made one" and momentarily lost in fantasy of their sense of inferiosity and loneliness.

Another group, Anglo-India would never let one forget that they are rulers and that natives are natives. As Ronny claimed, "We're out here to do justice and keep the peace... India isn't a drawing-room... we've got something more important to do."

The conflicts of the groups are obviously distinctive.

However, in the last section, a Coleridgean harmony is at last established. The Hindus can still enjoy their remoteness from public contention and live in old myths, and the friendship between Fielding and Aziz is the novel's chief demonstrating, that a bridge between the races might be built.

III. The Inner Passage

Unconsciousness belongs to pure unmixed life, consciousness to a diseased mixture and conflict of life and death. Unconsciousness is the sign of creation; consciousness, at best, that of manufacture.

--------Carlyle

"Machinery" was not just something found in factories, but something in the souls of men and in their personal relations.

-------Anonymous

The most confusing part in the novel may be Adela's adventure in a Marabar Cave. These caves are some myths of life:

'There's little to see, and no eye to see it, until the visitor arrives for his five minutes and strikes a match. Immediately another flame rises in the depth of the rock and moves towards the surface like an imprisoned spirit... The two flames approach and strive to unite, but cannot, because one of them breathes air, the other stone... The radiance increases, the flames touch one another, kiss, expire. The cave is dark again.’

'Having seen one such cave, having seen two... the visitor returns to Chandrapore uncertain whether he has an interesting experience or a dull one or any experience at all.’

Within the caves, when disturbed by human voices, is sounded a ‘terrifying echo’ which is entirely devoid of distinction.

The caves actually hint at something existing before Gods, before differentiation. They are the nourishers and givers of life, and the devourers and the seducers of it. They are the wombs and graves of the earth.

The light is brought into the cave from a newer and relatively rational world outside, but the caves make visible other flames which we are to imagine as inhabiting the stone from the beginning before man went out of the caves. Like the moving flames, consciousness and unconsciousness pursue each other in the novel, but they do not meet------and therein lies the world tragedy: the visitors to the caves and making a return from consciousness to the unconsciousness, going back to a prehistoric and prerational condition from which they have been released. Not to recognize this is not to understand the novel, for the main characters are defined by their reactions to the caves: some refuse to visit; other find them dull; still others experience there the hysteria of "panic and emptiness" like Adela Quested, the queer and cautious girl.

When she stepped inside a cave, a flame of unconsciousness was lit up, and slowly moved towards her. The heat of weather, the frustrating feeling in the cave greatly repressed her. She could not balance herself between unconsciousness and consciousness, her instinct and ration. The slowly approaching of the unconsciousness puzzled her, frustrated her and terrified her. The projection of unconsciousness lit up another flame of desire within her. She suddenly found her desire had waken up and there was no one for her to project it but Aziz ---- she had discovered that Aziz was a quite handsome man. But she just could not accept the projection of her desire towards him. Moreover, the profound shock of the leap from human status back to animal was echoing in the depths of her subconscious mind. The tragedy happened…

The cave, here shows its another form, on the inside is the anonymous, humorless region of the subconscious of those primal forces antecedent to character, in the outside is the world of ego, of consciousness, and history life in its tragedy, comedy, absurdity and mess. Thus, before we save the world, we must save ourselves, before we can know anything, we must know ourselves.

IV. E. M. Forster's Art and the Ending

Forster in this novel gives us a myth that throw the problems of

disorder into focus, reminding us that the follies are crimes of history stem

as much from man's failure of insight as from his wrong-doing. Sharing the

spirit of a Coleridgean artist, he was seeking a harmony between the world and

human beings between the consciousness and the unconsciousness. Forster's term

for his own doctrine is Art wit h a capital A. Art is not simply a created work

in painting, music or literature. Art is an idea of wholeness, a wholeness that

is greater than the sum of its parts. Art, for him, is the creation of wholes,

the harmonizing of contrarieties.

h a capital A. Art is not simply a created work

in painting, music or literature. Art is an idea of wholeness, a wholeness that

is greater than the sum of its parts. Art, for him, is the creation of wholes,

the harmonizing of contrarieties.

But as I have mentioned before, he is an artist living in an increasingly Benthamite society. The machine inevitably divides people, society, even everything into parts. He, in the end, could find nothing of wholeness to write with. Thus, when Fielding and Aziz rode in the season of monsoon at the end of the story,

"Why can't we be friends now?" said the other, holding him affectionately, "It's what I want. It's what you want.”

But the horses didn't want it---they swerved apart; the earth didn't want it, sending up rocks through which riders must pass in single file; the temple, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds, the carrion, the Guest House that came into view as they issued from the gap and saw man beneath, they didn't want it, they said in their hundred voices, "No, not yet," and the sky said, "No, not there.”

E. M. Forster put down his pen and said, "No, not yet. No, not there."

He turned from an artist to a critic.